academic work.

indigo waves

2022/2023royal college of art

ma architecture

︎view the online showcase here.

_

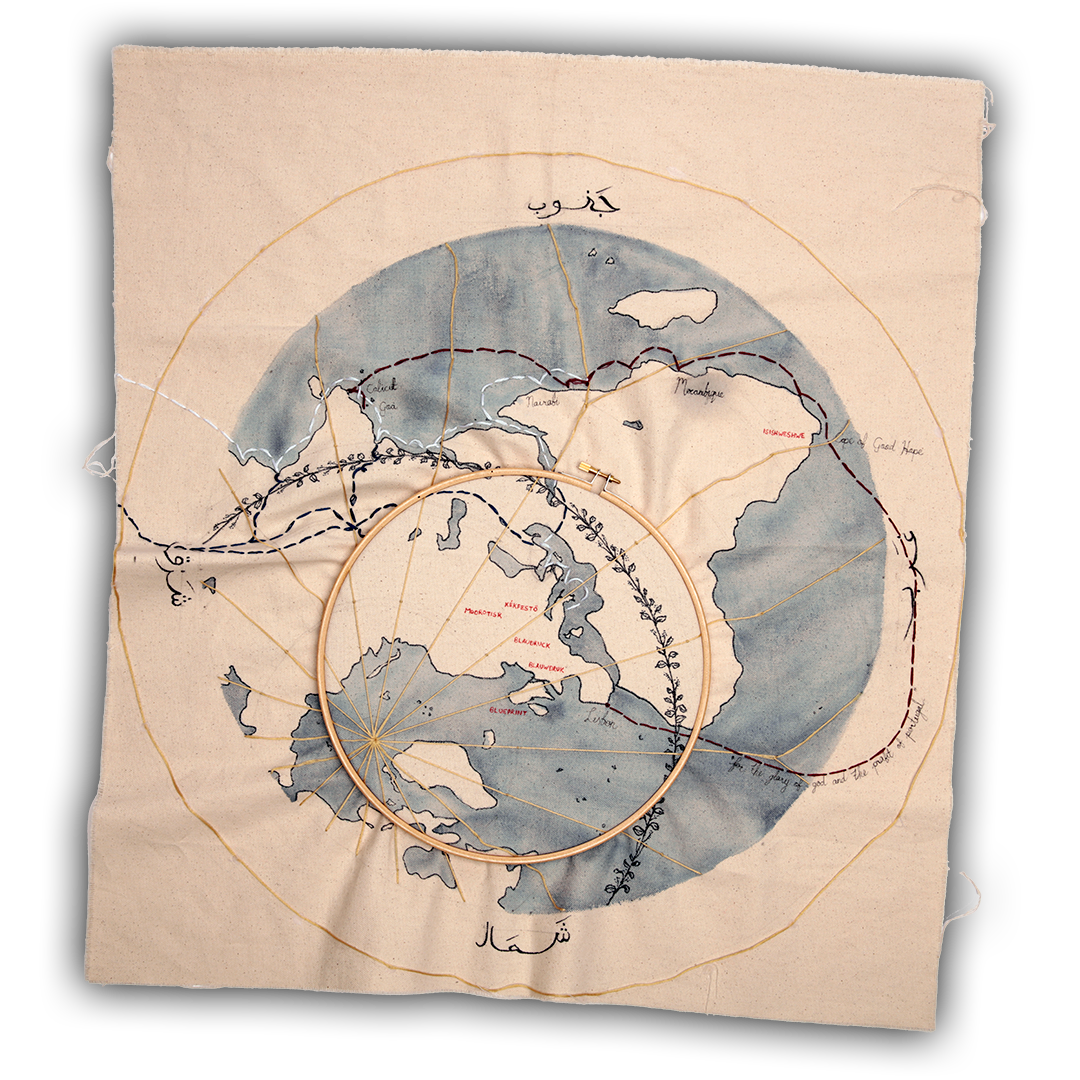

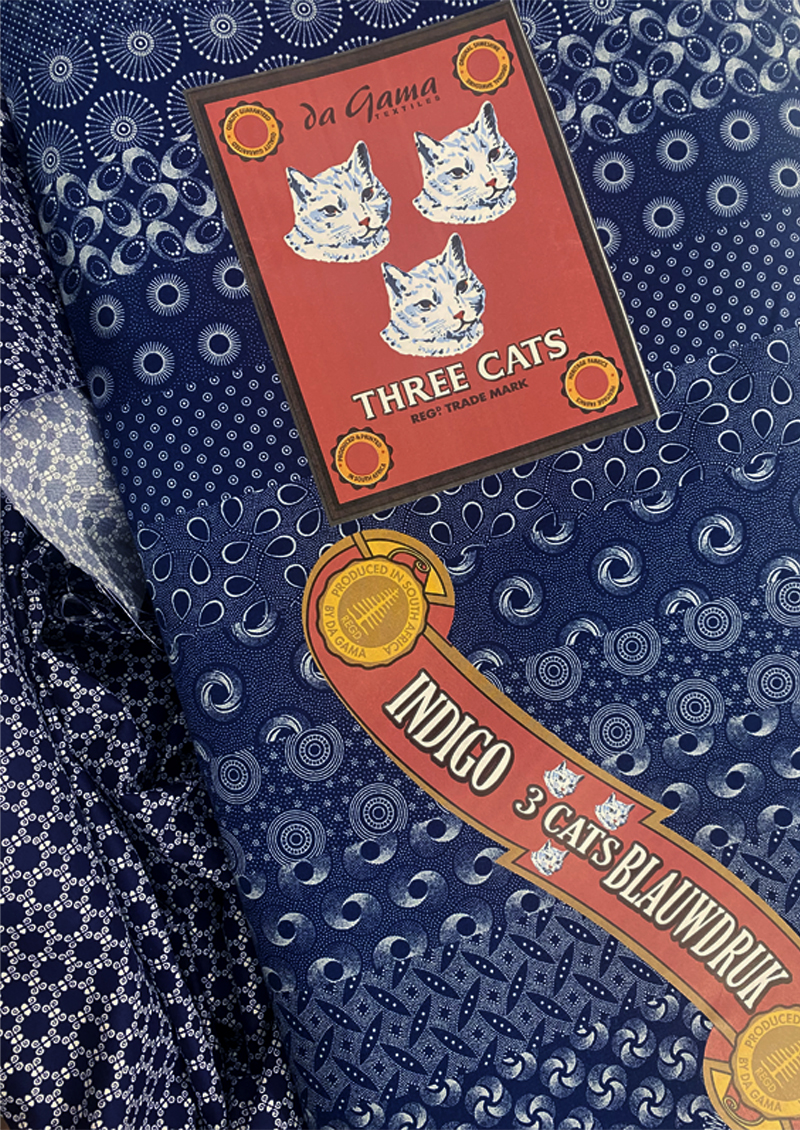

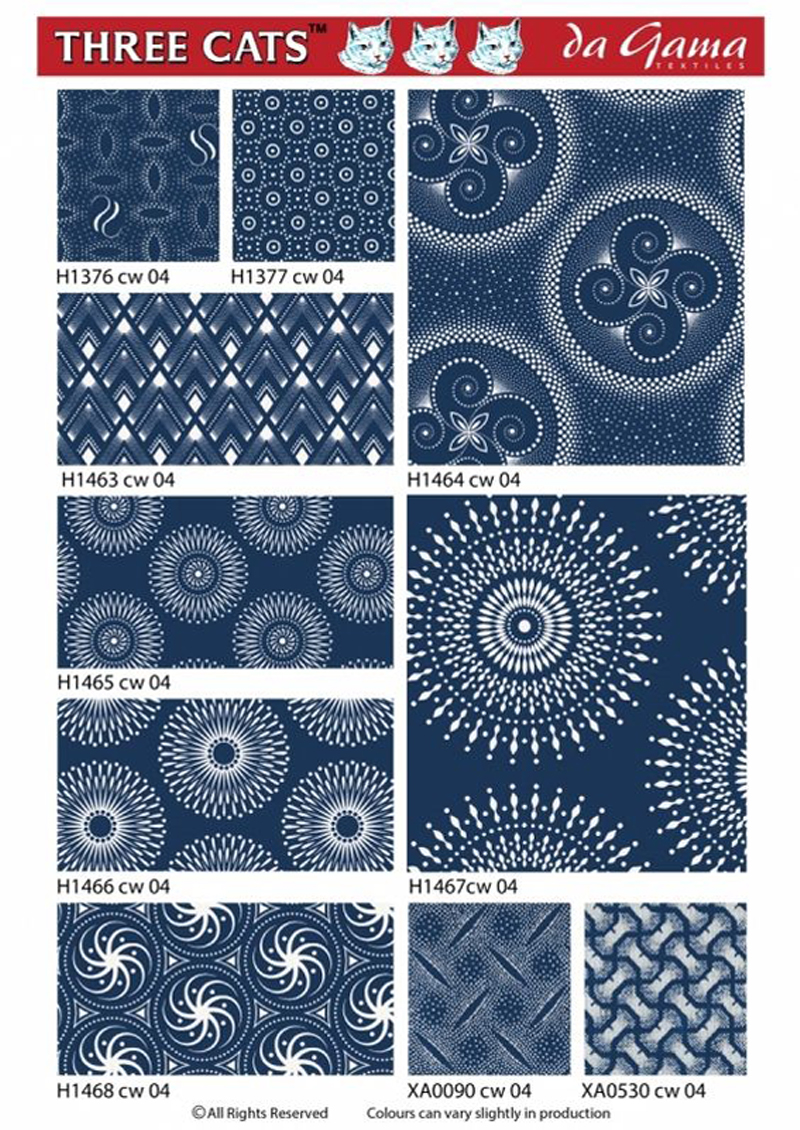

The project explores the hybrid identities of the Indian diaspora in South Africa through textiles, it delves into the rich history and significance of textiles as a medium for expressing cultural meanings and stories. The main focus is on isiShweShwe, an indigo-dyed blueprint textile with a complex history that originated in Asia, was adapted in Europe, and eventually reached Africa. The project explores how textiles can be used to express and negotiate hybrid identities within the Indian diaspora.

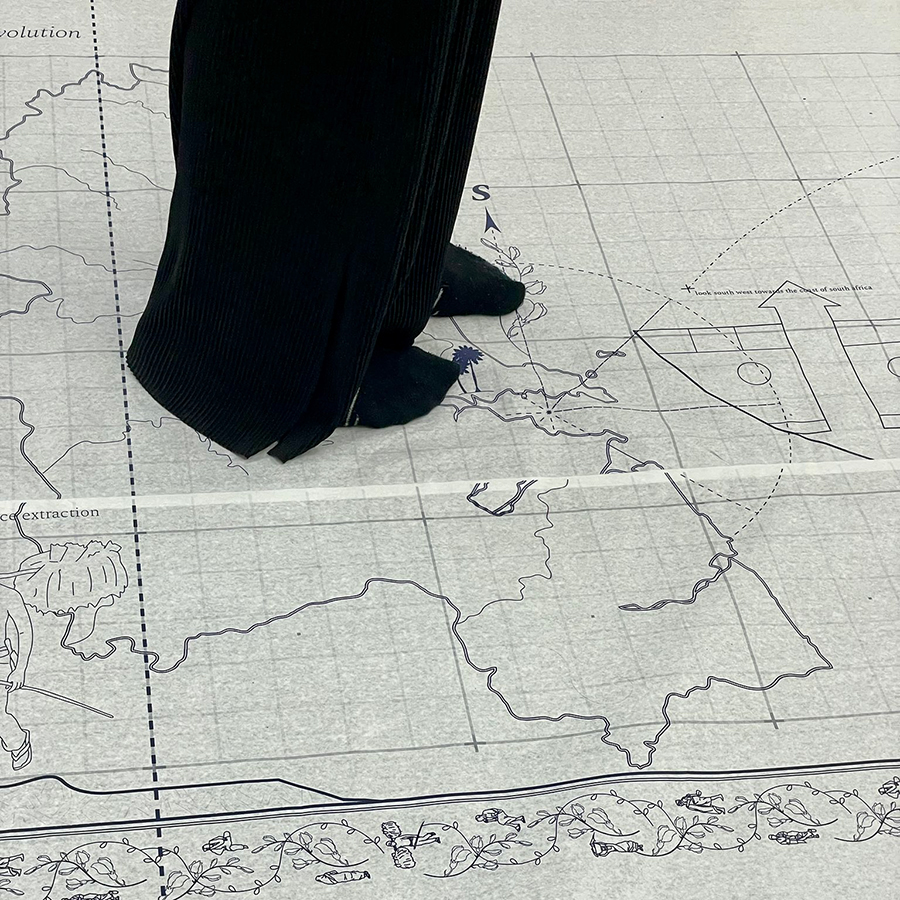

The research involves a series of embroidered maps and the use of the sari as a device to explore the intercontinental textile trade, colonization, and the displacement of bodies between India and Africa. Through the sari, the project aims to study the interplay between the body and space, demonstrating how the body's movement and interaction with the textile shape and transform the spatial environment.

Three performances are conducted using the sari to represent different aspects of identity and spatial relationships. The first performance involves wearing traditional clothing and explores how the body becomes an active agent in shaping and responding to the surrounding space. The second performance reinterprets the concept of a mosque as wearable architecture, allowing the individual to carry and inhabit the mosque as they move through different environments. The third performance, inspired by cultural practices and rituals, uses the dastharkhwan (tablecloth) to explore how individuals use space and the body to express their identity and beliefs.

The project aims to blur the boundaries between the body and space, viewing textiles as a means to extend the connection between the two and as a tool for design. It emphasizes the active role of the body in shaping and transforming spaces and seeks to explore spatial relationships through wearable devices.

Overall, the project brings together architecture, textile art, and cultural studies to unravel hidden stories woven within the fabric of our world, using textiles as a powerful medium for expressing and understanding hybrid identities.

gold dust

2021/2022royal college of art

ma architecture

_

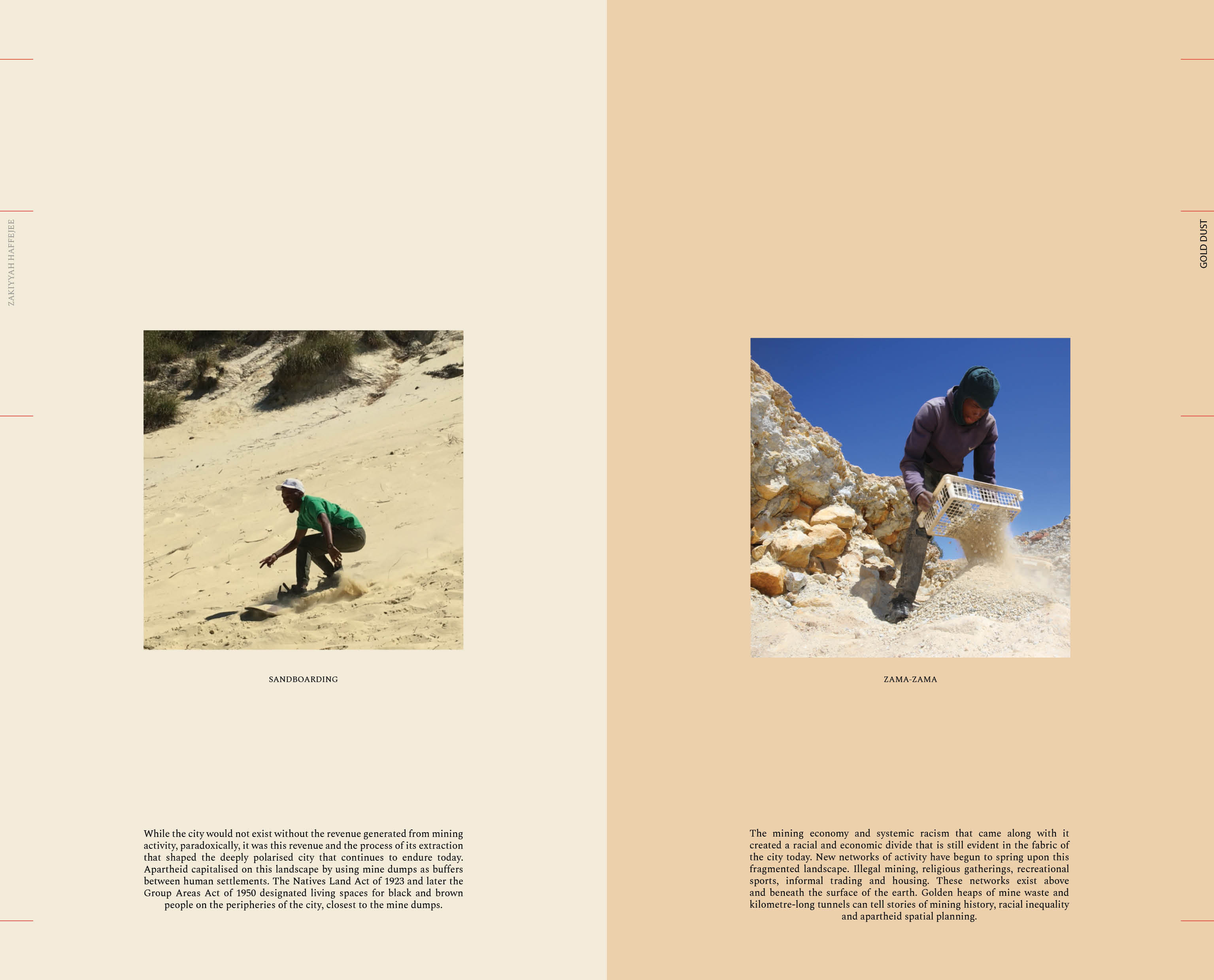

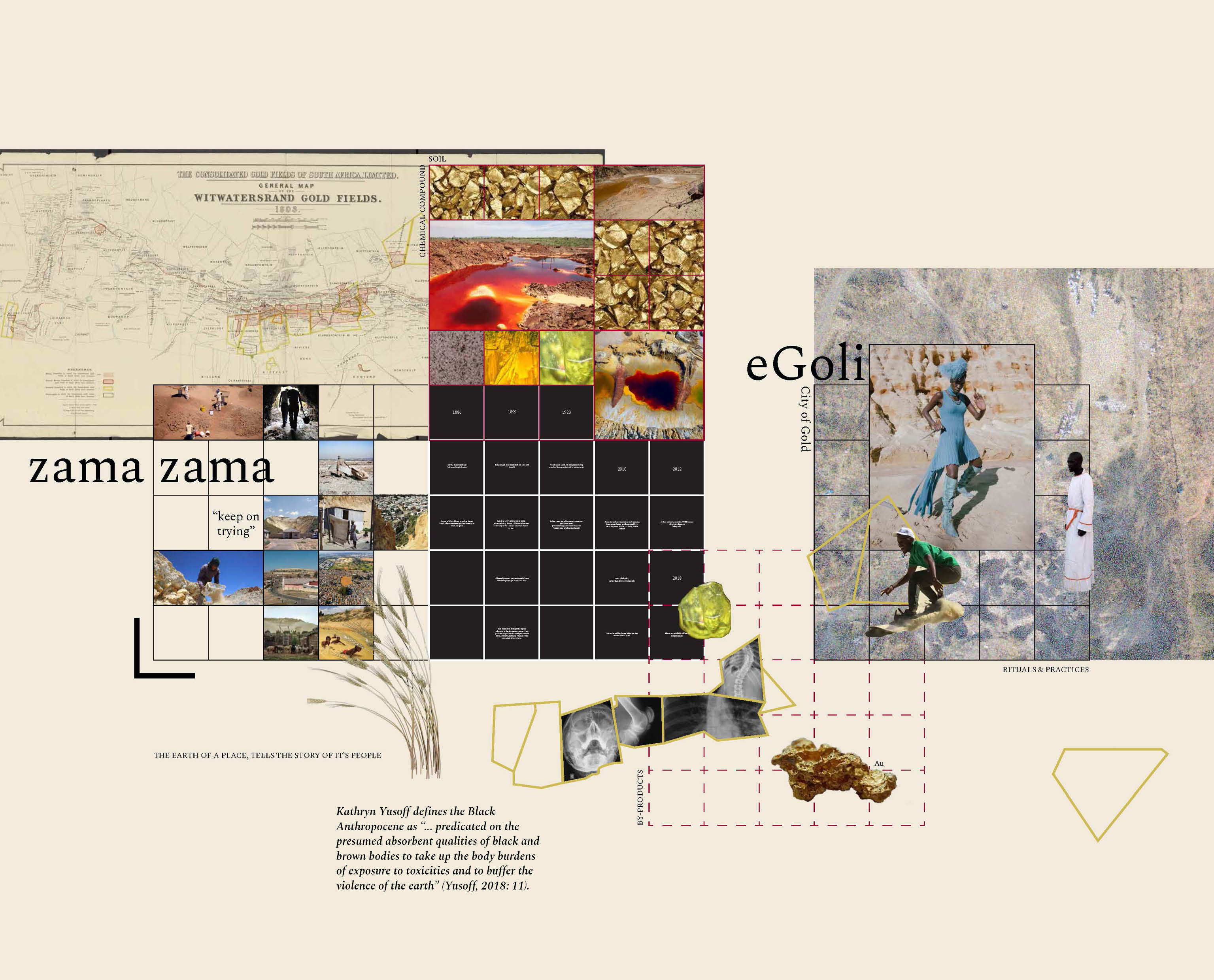

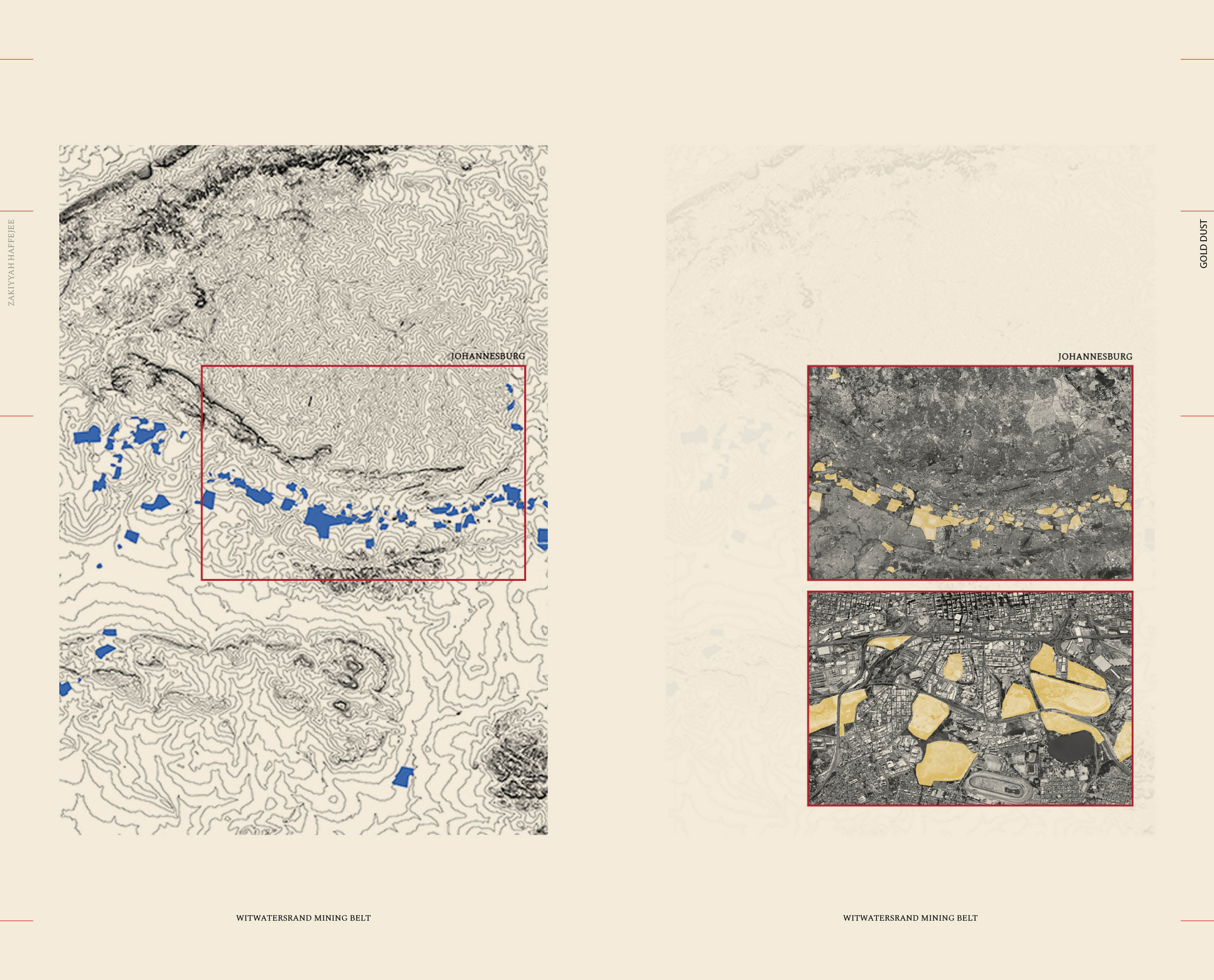

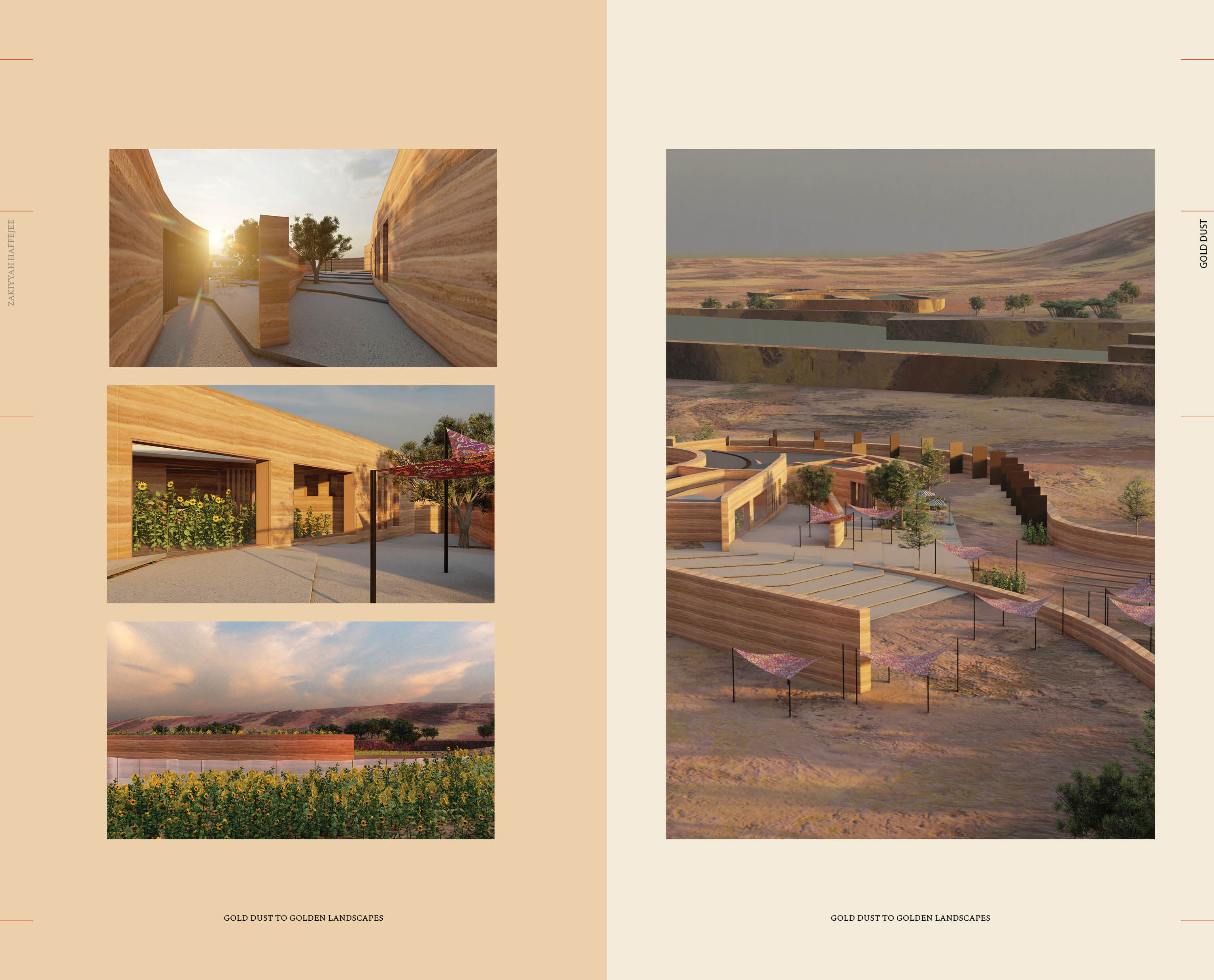

Johannesburg, fondly known as eGoli (The City of Gold) to locals is home to the largest and deepest gold mines in the world. The city was born in 1886 after the discovery of gold and is today South Africa’s largest city and one of Africa’s leading urban economies. Gold was found along the rocky outcrop of the Witwatersrand (The Ridge of White Waters) and very quickly attracted businessmen from all over the world, turning the grassy farmlands into a bustling mining hub. The continual extraction of gold along the Witwatersrand region has created a landscape fragmented by mounds of toxic waste. This landscape of extraction intercepts the city and has created pockets of uninhabitable space which presents challenges for the development and integration of the city. Golden heaps of mine waste and kilometre long tunnels can tell stories of mining history, racial inequality and apartheid spatial planning.

“The geography of Johannesburg reflects nearly a century of racially driven social engineering that reached a climax under apartheid…” (Campbell, n.d). Apartheid (literal meaning “apartness” in Afrikaans) was a tool developed by the white minority that used segregation as a form of control over the black/brown majority. The Natives Land Act of 1923 and later the Group Areas Act of 1950 designated living spaces for black and brown people on the peripheries of the city, closest to the mine dumps. Mine waste was used as a means for the purposeful separation of races, creating a landscape of barren and unsafe spaces. (Bremner, 2010).

“... predicated on the presumed absorbent qualities of black and brown bodies to take up the body burdens of exposure to toxicities and to buffer the violence of the earth” (Yusoff, 2018).

This work seeks to reveal legacies of racial capitalism that continue to manifest themselves in the absorption & buffering of black and brown bodies.

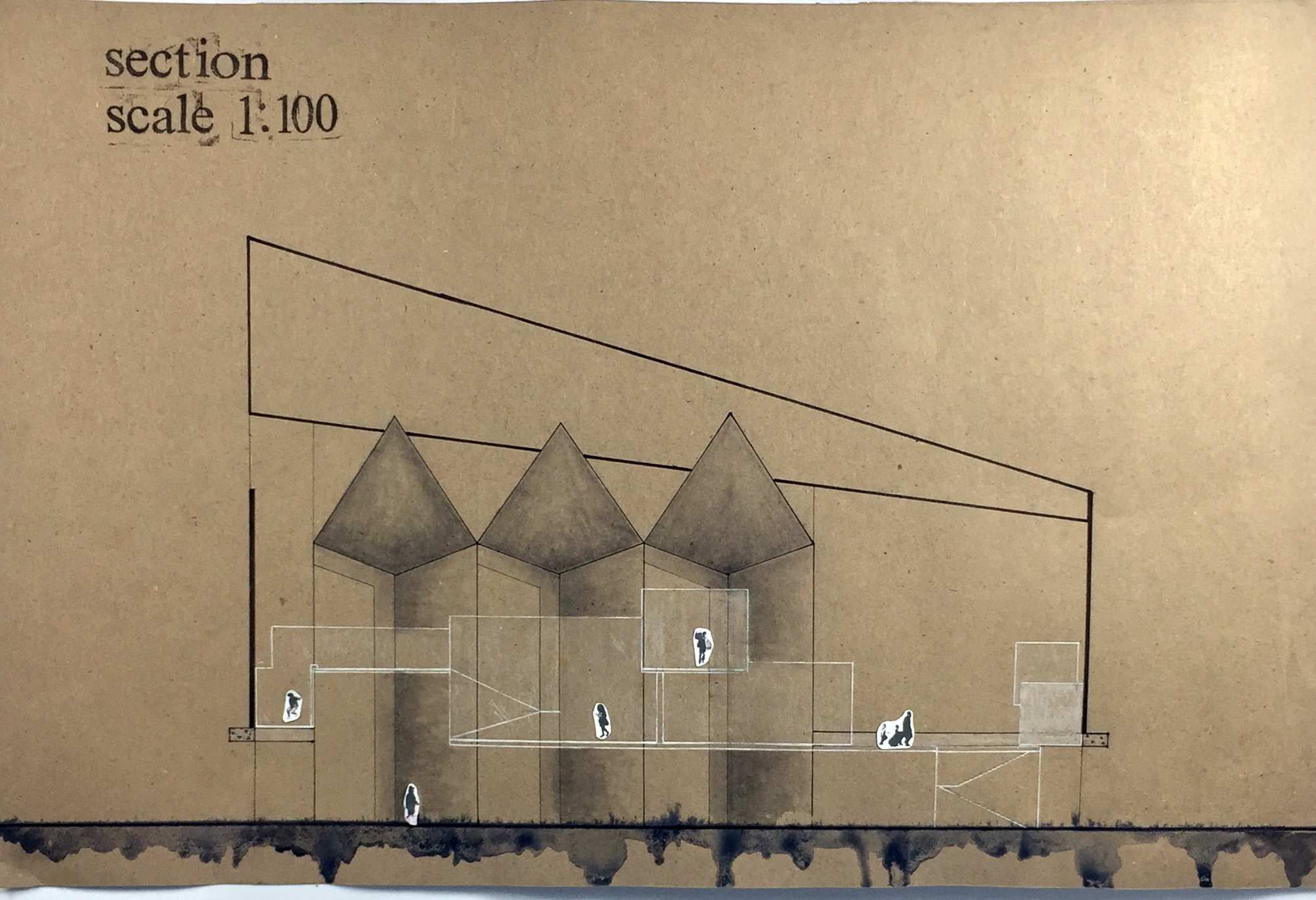

feminist city

2018university of johannesburg

btech architecture (applied design)

_

Designing shelters for female victims of domestic violence, rape and abuse should be considered from a feminist perspective; inclusive of theories of embodiment as the victims mental and emotional state is a key factor in her overall well-being.

Space becomes an important role-player in the healing process of victims. Our bodies respond to and anticipate the environment it is in. We can not seperate the space and experience, only our bodies from the space.

Therefore, our bodies become a site of experience.

Our designs should strive to merge function with experience; while providing basic human needs.

johannesburg 2050

2018university of johannesburg

btech architecture (applied design)

_

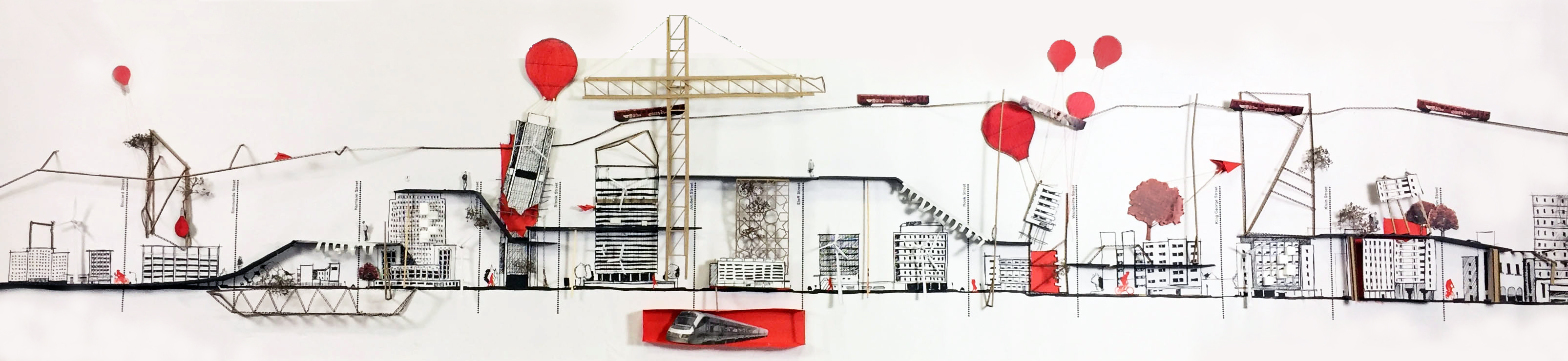

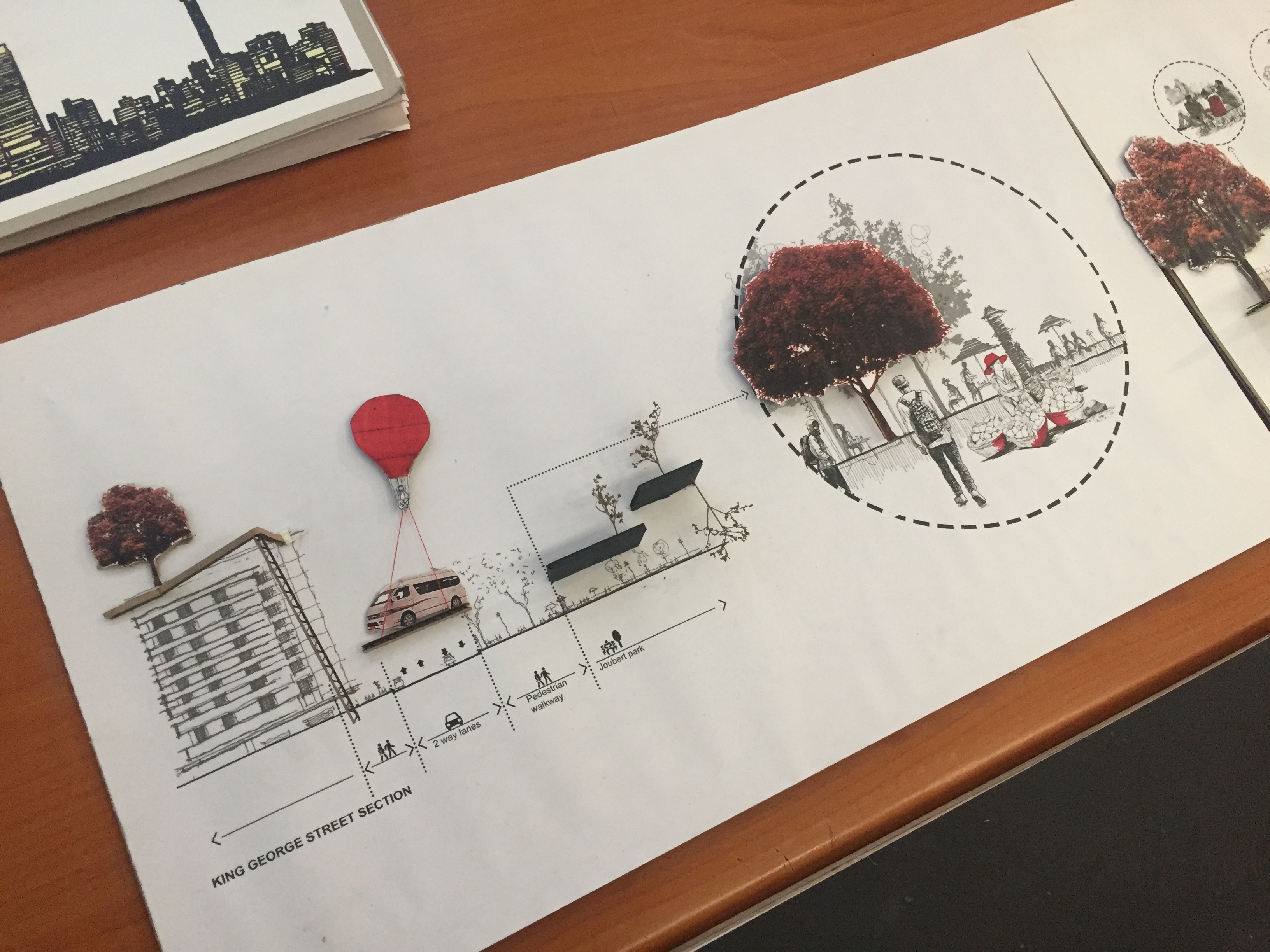

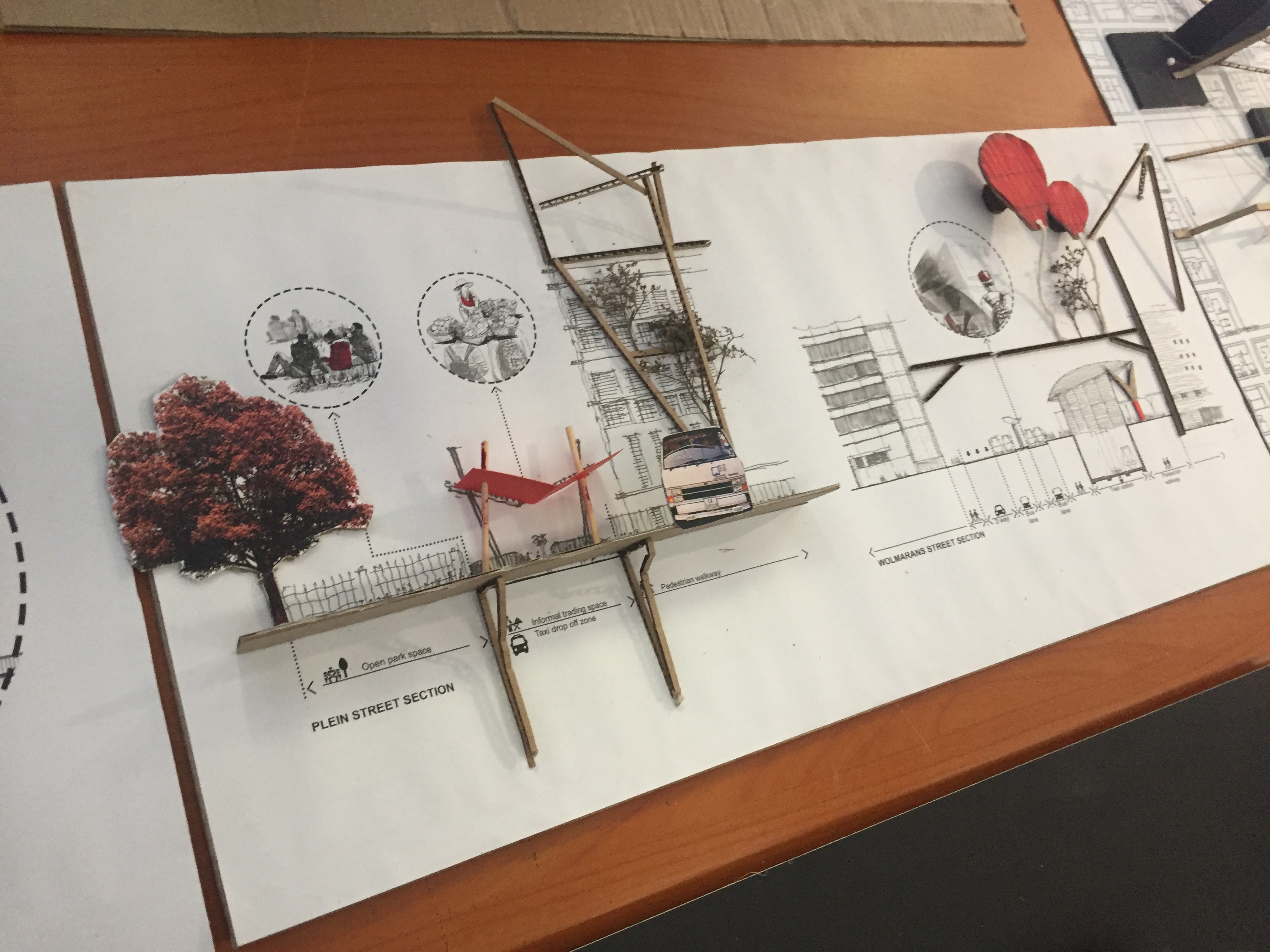

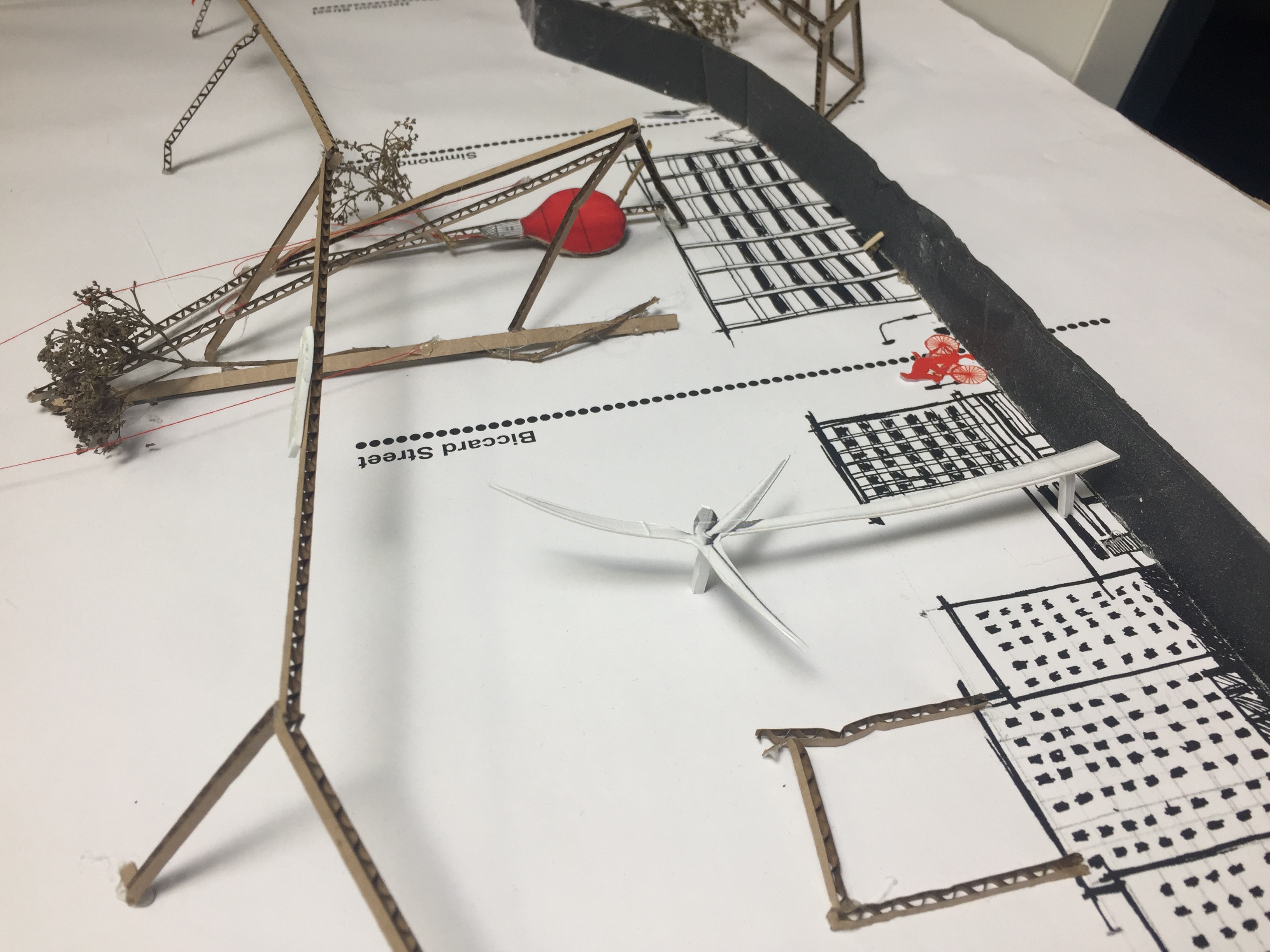

This project played with ideas of future cities. In response to the brief, Johannesburg 2050, we tested ideas of multi level transport systems and freeing up the ground plane for walking and cycling while disrupting the rigorous grid that is the Johannesburg CBD.

lothlakane

2018university of johannesburg

btech architecture (applied design)

_

A conceptual analysis and exploration into Tswana culture and land.

The site was set in the North West, in the village of Lothlakane, a traditionally Nkosi run village, approximately 30 minutes away from the city Mahikeng.

The task at hand was to create a space in which the elders could pass on knowledge of ancestry, agriculture and spiritual healing, while respecting the land.

multi-faith spaces

2017university of johannesburg

diploma architecture

_

Perceptions of spirituality are often misconstrued by societal ideals.

Spirituality is something that cannot be seen but only experienced or felt. Every individual experiences spirituality in a different way.There is no right or wrong.

Spirituality is something that includes a connection to something bigger than ourselves. It is a human experience that at some point touches us all.

In multi-faith rooms, people of all faiths, as well as those of no faith share a space that takes on a set ofsacred modalities. Multi-faith has become the default form of religious space in hospitals and airports and has introduced sacred space to places like shops, football grounds and offices where noneformerly existed.

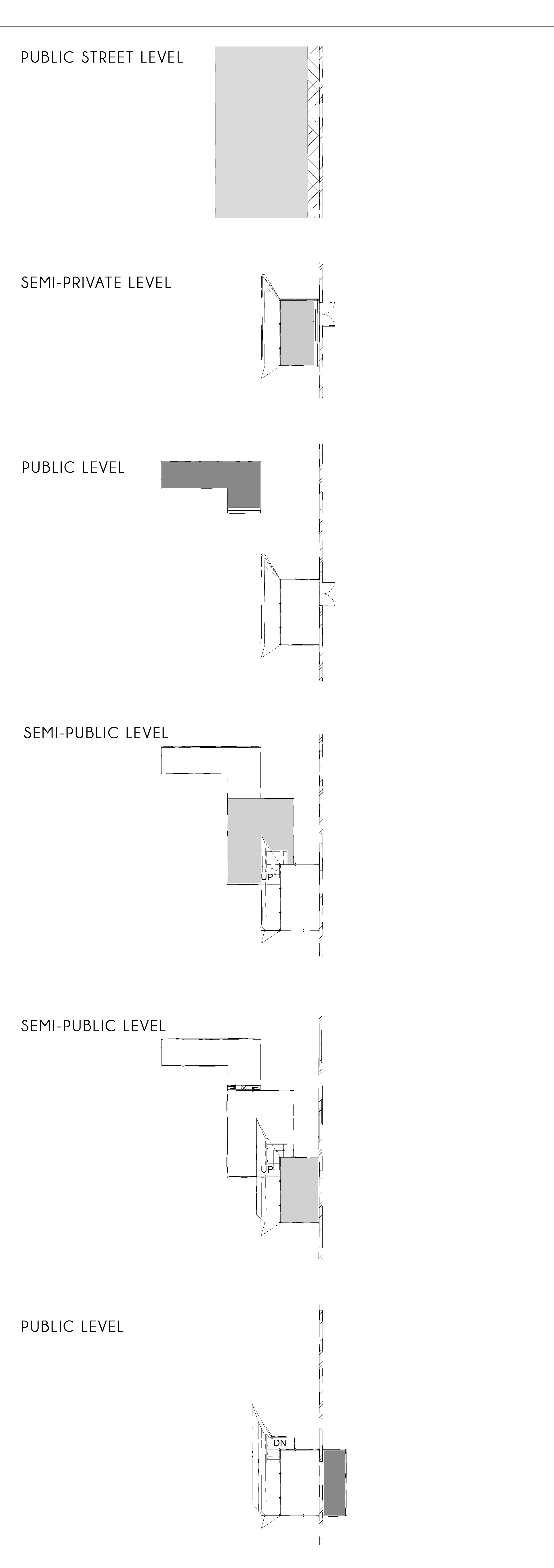

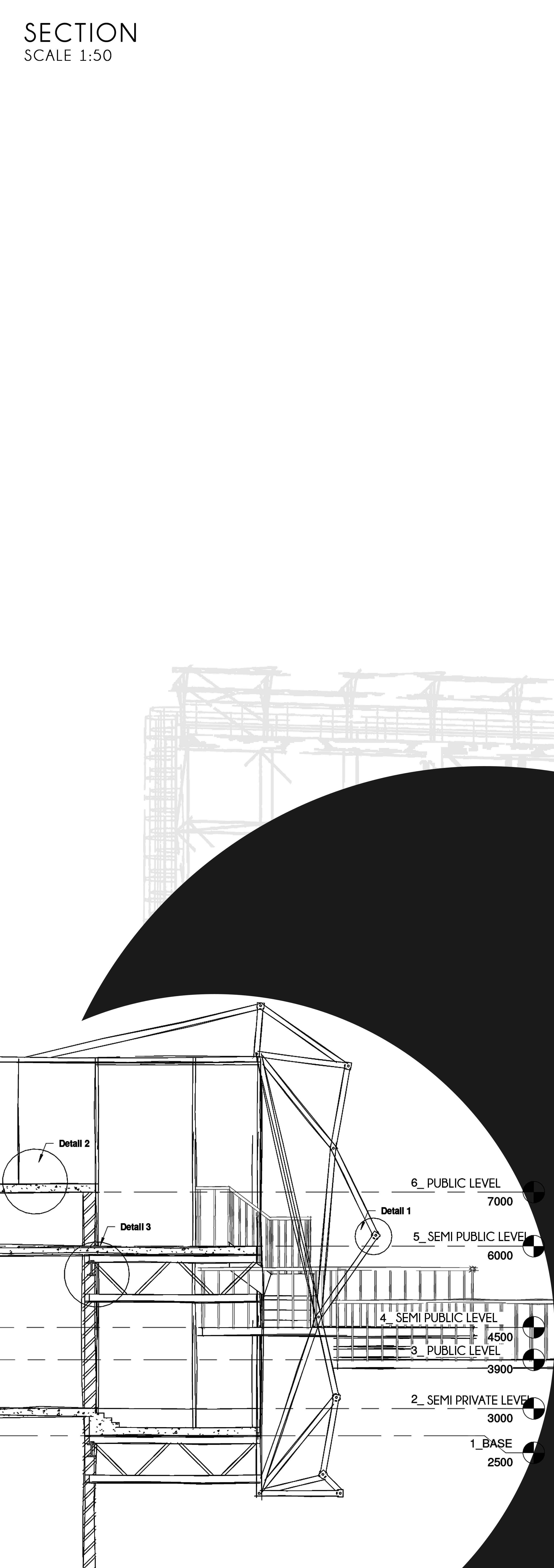

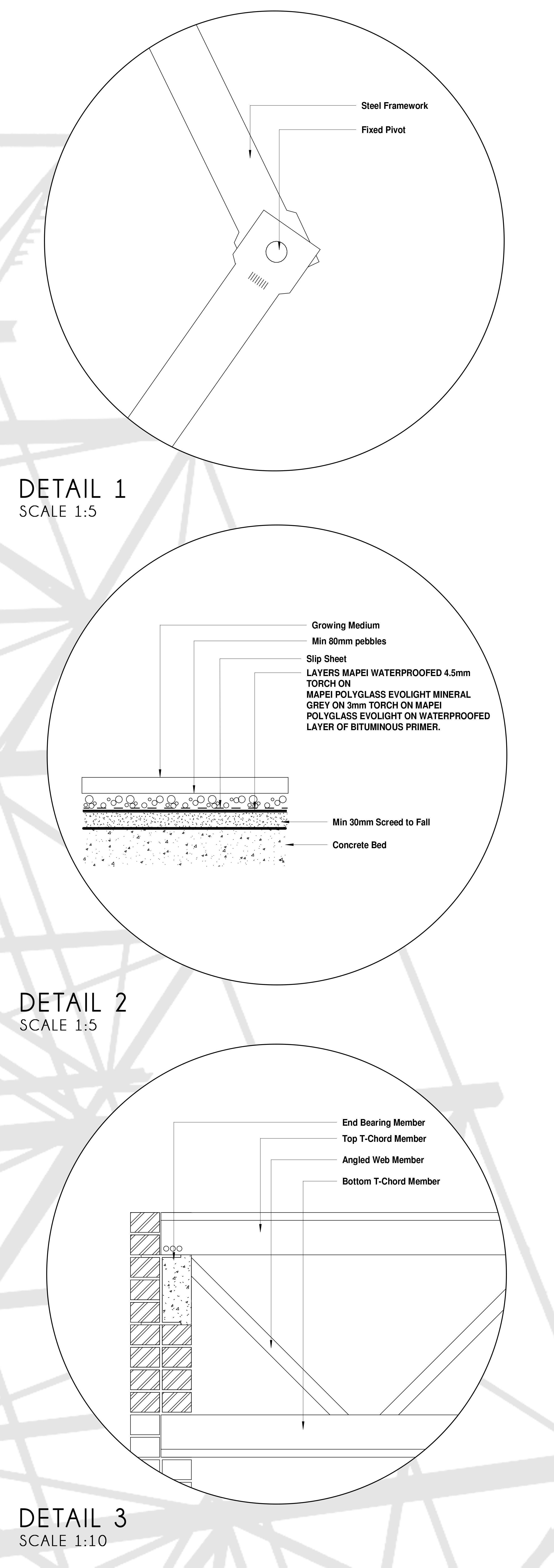

protest city

2017university of johannesburg

diploma architecture

_

The nature of architecture within the urban framework that we live, sleep and work in today, is categorized by the amount of money in your back pocket.

“Cities have always struggled with the tension between the different needs of social classes who share the space.” (Chris Mills, 2015)

Defensive architecture, sometimes referred to as hostile architecture or anti-homeless architecture is 'designed' to deter 'unruly or unsightly' behaviour within spaces. These modifications are often too subtle to be noticed by the general public, but are put in place to discourage loitering, sleeping and sitting. By implementing such measures, not only are we making it impossible for the dispossessed vagrant to rest his weary body, but we also make it difficult for the elderly, for the cripple and for the dizzy pregnant woman needing to take a seat; to name a few.

My intervention, latches onto a private sector building designed for a ‘certain class’ of people and ensured to keep others out. It questions levels of public and private interaction and provides spaces for all classes. The parasitic structure is inspired by works of graffiti that appear overnight in protest of certain causes.

If defensive architecture is the protest, then by challenging this notion, ultimately we would be protesting the protest.

arrival

2017university of johannesburg

diploma architecture

_

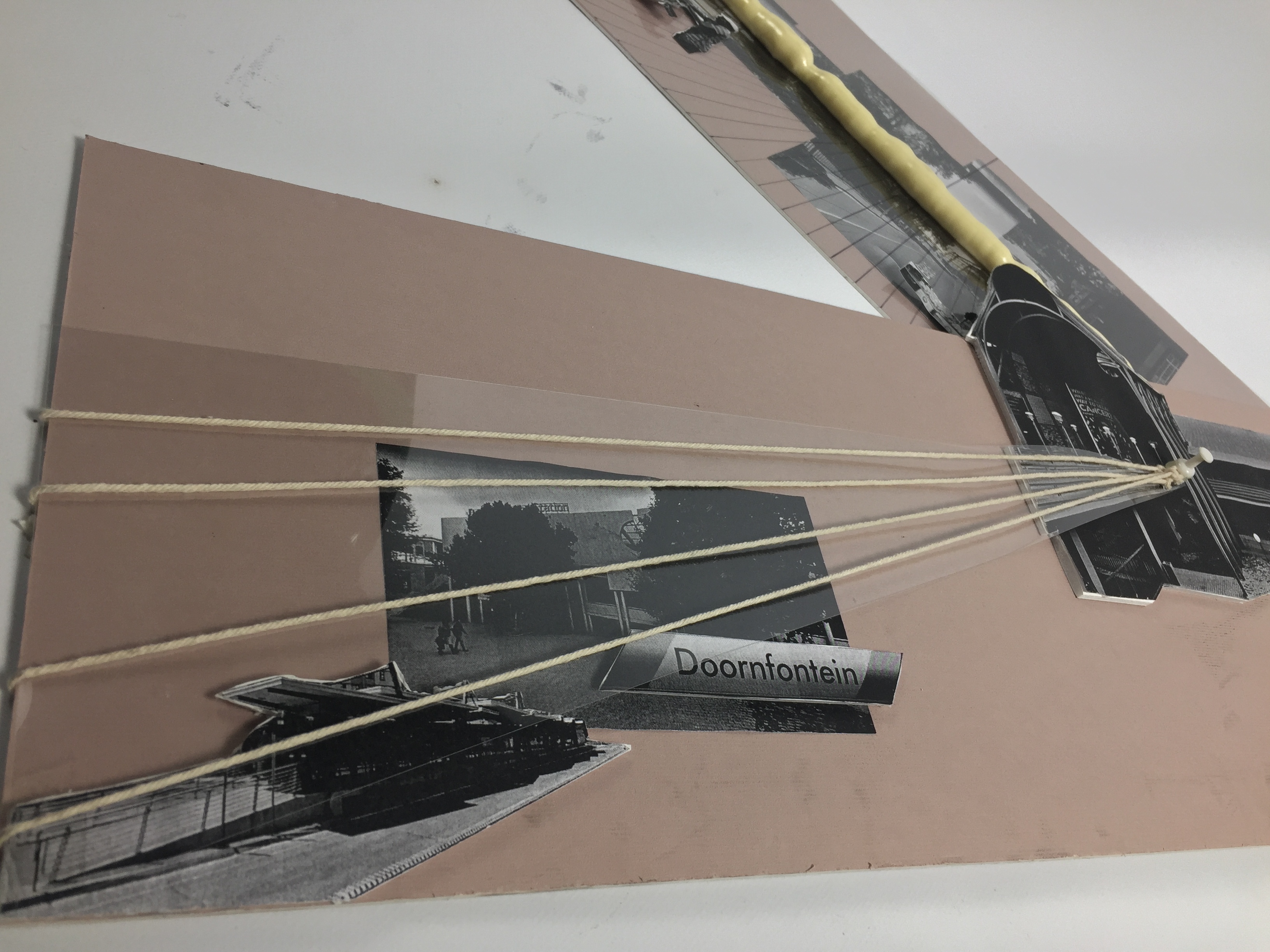

The suburb of Doornfontein is situated on the outskirts of the Johannesburg CBD. It is a former miningsuburb. The university planted itself in the midst of the city before infiltratingits surroundings. As the university grew larger and required more space, it spread itself out intoDoornfontein like a PARASITE taking over all that it touched. It privatised public roads as well as manypublic religious buildings.

The city is a living organism in its own right. Powered by a network of streets that allow people to haveaccess to proximities as well as form networks of their own. Like the body of a living organism,Doorfontein has its own intricacies that work together in order to keep the city alive. These include theinfrastructure, the buildings, the spaces, and most importantly the people that give the city character.

The city is planned out such that it forms a grid system. Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan arefrequent intersections and orthogonal geometry to assist in pedestrian and vehicular movement.The geometry helps with orientation and affords people a choice in which routes to take as they so

desire. The periphery of the university is surrounded by a boundary that disturbs this geometry andseparates two communities. Your community is determined by the side of the fence that you’re on.Because of the roads being privatised, and the harsh boundary surrounding the campus, access is limited to routes people may desire to take.